latest messages

Small Boat, Deep Water

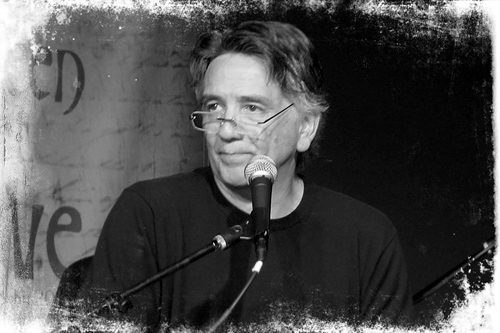

Dave Brisbin 6.22.25

Chances are, if you were raised in a Christian tradition, you learned that doubt was the enemy of faith, the opposite of faith, if you had any doubt at all you had no faith. Such learning goes deep and doesn’t go away without a fight. Makes us so hard on ourselves, feeling the inevitable doubts of uncertain human life only to pile on the condemnation of childhood.

Making matters worse, we read the gospels to see the first followers of Jesus drop their nets, their entire lives, to follow him at their very first meeting. These were men with wives and children, livelihoods supporting their households. They left all that at the first meeting with a stranger? Is that the bar for faith?

read more

Luke relates that Jesus gets in Peter’s boat at the end of an unsuccessful day of fishing and asks him to put out a little way from shore so he could address the pressing crowd. After speaking, he tells Peter to put out into deep water where they catch more fish than they can haul. Putting out a little way, little risk, to hear the logos or propositional truth is always the first step. Putting out to deep water to hear the rhema or living call to action is the moment truth becomes more than we can haul. Even then, Peter is still wracked with doubt.

Doubt is not the opposite of faith. Faith needs doubt as courage needs fear. Answering the call in spite of our doubts is the best humans do.

Keeping Awe Alive

Dave Brisbin 6.15.25

Past week brought a series of headlines each pre-empting each other’s news cycle. Against a backdrop of wars in Ukraine and Gaza and the disruption of a new US administration intent on radical change, protests and riots broke out in LA, then aerial offensives between Israel and Iran, political assassinations in Minnesota, more protests nationwide. Huge issues we can’t ignore, that demand a response, a personal way forward.

In the midst of it, I receive an email about a meditative practice of “moving our awareness into our hearts, letting our vision arise from a place of integration rather than analysis, receptivity rather than grasping after things we desire.” Though it stood right at the heart of contemplative practice that I’ve been championing for decades, this week, it read like an anemic retreat from action, naïve, even irresponsible in the face of all that needs doing. Silence is the cornerstone of contemplation, but for many, silence is mere complicity. We all want to feel relevant, do something significant, so what is a responsible response?

read more

Awe is an encounter with vastness, even if small, beyond our frame of reference, challenging everything we think we know. What we think we know, no longer awes us, so to be awed is to accept we may be wrong, that we don’t know everything. Awe alone diminishes our sense of self, restores the humility and balance needed to see our connection to everyone and everything, even a sparrow on a battlefield.

Contemplation keeps awe alive. Awe is silence that is not complicit…essential preparation for speaking and doing what actually heals.

Graduating Tribe

Dave Brisbin 6.8.25

A man asks me about Jesus’ saying that if we believe in him and his works, we’ll do the same and greater works than he. He’s troubled by the verse because he’s not doing the works that Jesus did, let alone greater ones, so does that mean he doesn’t really believe? I ask him what works of Jesus he’s looking to do. Well, it has to be the healings and miracles, right? And therein lies the rub.

The church hasn’t known what to do with this verse for the same reason, usually limiting it to Jesus’ immediate inner circle who performed healings and miracles in the gospels. But if Jesus’ message doesn’t apply to us, why read it? Or maybe we’re just misunderstanding which works Jesus means. Nothing focuses the mind like a deadline, so you can bet the last words a person believes they’ll say to you will be the most crucial they have to offer. Jesus’ last words to his friends were to love each other as he had loved them, that people would know they were his followers by their love. Not theology, ritual, or miracles.

read more

Pentecost, a symbolic fifty days after Easter, is the moment Jesus’ followers experienced their own spiritual liberation. Their loss at Calvary was the beginning of a wilderness journey that had to be taken without Jesus. As long as they were with him, they continued to think tribally, physically, literally, missing Jesus’ real works. He said it was to their advantage that he go, so they could identify with God’s spirit—always there, but invisible to tribal eyes.

When they speak that day, and everyone hears them in their own language, what better way to understand their graduation from tribe, from the confines of ethnic identity to God-in-all identity, the real work of Jesus.

Hidden in Each Other

Dave Brisbin 6.1.25

What is the most important goal of your spiritual formation?

You might instinctively say love. Learning to love, practicing love. Good answer, but until we carefully define it, love may not help direct us. Rather than a feeling or behavior, love is simply identification with the beloved. When we identify—see ourselves in the other, a fellow imperfect human, an extension of us—whatever we do for them, we do for ourselves. To experience that identification is love. And vice versa. So…

…the goal of our spiritual formation is identity.

We need to be able to answer the question, who am I, and its twin, why am I here—or our lives will always be random with respect to our awareness and choices. And since love and identification are hopelessly entangled, a critical truth is laid bare: we will never find our identity in isolation, in the abstract, but always and only in connection with each other, with everything, with God’s presence.

read more

Jesus is all over this. When he says we have to lose our lives to find them, he’s talking about losing our isolating thoughts about ourselves in order to come back home, to reconnect and identify. Clinical studies have now shown that when we experience awe—defined as encounters that are vast, beyond our current perceptual frames—our sense of self is diminished, a first domino creating a chain breaking down social barriers and increasing sense of meaning. Whether in nature, prayer, or relationship, our spiritual formation is nothing more than serial awe inducement…bringing us back to the vastness that takes us out of ourselves.

True identity can’t be conceived, named, or described. Soon as we do, we’re back in isolation, separated from the only place we’ll find it. True identity can only be experienced in moments of awe, pulled outside our thoughts to find it hidden in each other. If we’re looking for identity all by itself, we’re looking in the wrong spot.

Identity Shift

Dave Brisbin 5.25.25

If I asked you who you are, how would you answer?

Almost everyone I’ve asked, including myself, has answered with a mix of the roles they fill, the accomplishments they’ve accumulated, and the attributes they exhibit. Roles, accomplishments, and attributes describe the human container we inhabit in this life, the whole with which our egoic consciousness identifies. We think we are our roles, accomplishments, and attributes until we step out of our containers to find a deeper identity underneath. We’ve all stepped out at moments of peak experience, but we don’t shift identity that fast or easily.

We fear the loss of our container to death, illness, age, trauma as much as we identify with it. And we identify with it exclusively until we intentionally practice the experience of stepping out.

read more

The freedom of the truth Jesus offers is that who we really are can never be lost. Ever. Not even in death. Any identity imagined as separate from any other identity, from God’s identity, is illusion, so to strip the illusion is to see that we and the Father are one: true identity.

Jesus’ Way is relinquishing everything that can be relinquished until only that which can’t be relinquished remains. The point of any spiritual journey is to arrive at the ground of this irreducible presence, an identity that can’t be lost, but costs us everything to which we cling.

The Life in Death

Dave Brisbin 5.18.25

Two events converged in my mind last week.

My wife and I picked up the ashes of a friend we’d been helping take care of for the past few years…and our faith community turned eighteen years old. Nothing like an anniversary to open the memory faucet, and maybe because of our friend’s death, the serious illnesses of many others, and my own advancing age, my memories were not focused on timelines, but the long parade of people who have meant so much. Those who have stayed, moved on, and especially those who have passed on.

They have been reminding me of the brevity of life, to make my time count. Not morbidly in a pressured way, but gratefully, aware of the gifts they gave me in our short spans together. Each of four men who helped found and lead our community had a particular gift he exuded, lived out most likely unintentionally, and of which I was unaware at the time. It’s perversely true that it’s harder to see the gifts others are giving while they live. Maybe because while ongoing they’re taken for granted, or because always mixed with inevitable faults and annoyances, the prophet is not honored if too familiar.

We don’t know what we got til it’s gone.

read more

To live with presence, passion, humor, devotion is to immerse so fully in life, we step outside the container we will leave at death, realize that all our fear exists only in our minds. Not in life. Or in death. Fear is a mental construct that we can take off like a dirty shirt. We will always fear the unknown at first, but our teachers, living and dead, are showing us in their most unguarded moments, that we can loosen the bonds that hold us inside our fears and experience the life that exists even in death.

Restoring Mom

Dave Brisbin 5.11.25

Our English words patriarchal and paternal descend from the Latin word pater, father. We know about patriarchy—society organized around male domination, often to the point of excluding women—but paternalism is restricting the freedom and autonomy of others under the guise of protecting their own welfare. The US started out patriarchal but not paternal. We didn’t allow women to vote until 1920 but also didn’t collect income tax until 1913, generally leaving people to fend for themselves for better or worse. Today, we’re thankfully much less patriarchal, but much more paternal.

On Mother’s Day, this is something to consider, because the church also been shamefully patriarchal, reflecting the culture around it. But since scripture does appear to portray God as male, is God patriarchal and/or paternal? We may wish God to be more paternal, happy to give up freedom for better risk control…but patriarchal? Male?

read more

Jesus always led with mother first, breaking ritual and social barriers in order to establish compassionate relationship before he ever instructed paternally. Father may symbolize strength, but without Mother, there is no reason to be strong. Scripture shows us a necessary and complementary balance, but more essentially, that we will never know Father God until we first experience God as Mother. All of God.

Already Free

Dave Brisbin 5.4.25

The most damaging attitude toward life and spirituality is…wait for it…passivity.

Passive people feel their actions are insufficient or that they have no real choice at all, which makes them victims—defined by choicelessness. Victims are always waiting, never in the present, looking toward some other moment when circumstances may change or someone, God, saves them from their circumstances. People with victim mentalities are passive-aggressive in their interactions with others, finding indirect ways of meeting needs and expressing anger or frustration without ever directly confronting core issues.

As damaging all this is to human relationships, it’s catastrophic to spiritual ones. And yet, a passive, victim mentality is seductive, as comforting as a warm blanket, often nurtured for lifetimes. Having no choice also means no blame, no responsibility or need to act. Innocent of all charges. An innocent is not responsible either—kind of the flip side of a victim, and it’s comforting to imagine ourselves as innocent.

But we were not created to be innocent. Certainly not to stay innocent.

read more

It’s scary to be responsible. Overwhelming at times.

We all become victims when personal choice is removed, and as much as that hurts, the relief it can offer in ongoing passivity, the luxury of not having to choose or act, can bewitch us. If we’re waiting for God to save us, he’s not coming…because he is already here. All poured out. If we’re waiting, we’ll never see the truth. That we’re already free to choose what has already and always been freely given.

Between Freedoms

Dave Brisbin 4.27.25

We’re back in count again.

We just finished counting forty days of Lent, and now we’re counting again. The count of Lent signifies a time of preparation for Easter, and the count now is also preparation for a second liberation on the fiftieth day after Easter—Pentecost.

Our liturgical calendar is overlaid on that of the Jews, who for 3,500 years have counted seven weeks of seven, forty-nine days plus one, from the second day of Pesach/Passover to Shavu’ot/Weeks. Originally a festival marking the barley harvest, Passover became linked with Exodus, the physical liberation of the people. Shavu’ot, at the wheat harvest, was linked with the giving of the Law on Sinai, the spiritual liberation of the people and the beginning of a deeper relationship with God.

read more

The shape of their journey is ours as well. If we answered the call to seek something greater than ourselves, joined new communities, accepted new beliefs and traditions, we’ve had our physical Exodus, liberation from the illusion of separation. But this is just the beginning. We remain in count. Calvary, the loss that begins the wilderness of stripping off all to which we cling, is the fulcrum between our two liberations.

The way to Pentecost begins at Calvary and is traveled living as if God and God’s promises are more alive than life itself.

Meaning of Resurrection

Dave Brisbin 4.20.25

Cross and resurrection form the crux of Christian tradition, but whatever these events were historically, if we merely revere them from a distance of two millennia, we are missing the point of the gospels. These events realigned every detail of the lives of Jesus’ closest friends and followers, but as long as they remain historical events and theological concepts, they won’t realign ours. If the resurrection is to have the power now that it had then, we need to know where to look for meaning.

We naturally focus on the supernatural event, fighting and debating, but have you noticed that the gospels don’t show us the event at all? Makes us crazy looking for literal details, for certainty, but in the gospels, the resurrection happens offstage, in the blink of a hard cut. The story picks up afterward, following those Jesus left behind and their all-too-natural, human reactions. The gospels show us exactly where to look for meaning—not in the miracle itself, but in how the miracle affects our lives.

The question isn’t whether you believe…it’s what difference it makes that you believe.

read more

Whatever the resurrection literally was two thousand years ago, if we don’t re-experience intimacy with Jesus now, in prayer and every face and embrace, every detail of our lives, we may say we believe, but re-animation, rebirth, will elude. The meaning of resurrection, like kingdom, is not out there somewhere to be observed, but within us to be tasted and seen as life that is always new and always alive.