Deconstructing Scripture

The ancient sacred writings of of the Hebrews and early Jewish followers of Jesus do not immediately convey their original meaning to Western readers–ancient or modern. By the fourth century, church doctrine and law was being formulated on a Western and more literal understanding of the text, and as time has passed, it has become only harder for us to understand Jesus’ original message. These podcasts break down–deconstruct–the literal meaning of our English translations to put them back into their original context, language, and worldview–essential to understanding what the writers were originally trying to communicate.

Meaning of Resurrection

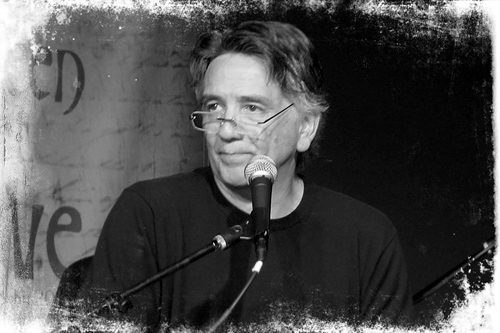

Dave Brisbin 4.20.25

Cross and resurrection form the crux of Christian tradition, but whatever these events were historically, if we merely revere them from a distance of two millennia, we are missing the point of the gospels. These events realigned every detail of the lives of Jesus’ closest friends and followers, but as long as they remain historical events and theological concepts, they won’t realign ours. If the resurrection is to have the power now that it had then, we need to know where to look for meaning.

We naturally focus on the supernatural event, fighting and debating, but have you noticed that the gospels don’t show us the event at all? Makes us crazy looking for literal details, for certainty, but in the gospels, the resurrection happens offstage, in the blink of a hard cut. The story picks up afterward, following those Jesus left behind and their all-too-natural, human reactions. The gospels show us exactly where to look for meaning—not in the miracle itself, but in how the miracle affects our lives.

The question isn’t whether you believe…it’s what difference it makes that you believe.

read more

Whatever the resurrection literally was two thousand years ago, if we don’t re-experience intimacy with Jesus now, in prayer and every face and embrace, every detail of our lives, we may say we believe, but re-animation, rebirth, will elude. The meaning of resurrection, like kingdom, is not out there somewhere to be observed, but within us to be tasted and seen as life that is always new and always alive.

Threat of Clarity

Dave Brisbin 4.13.25

Very few of us live in the real world.

Like avatars in a gamescape, we live in a world created by our own thought patterns, which are in turn created by our core beliefs—deeply held, fundamental assumptions about ourselves, others, and the world. Hiding in our unconscious, core beliefs are as unquestioned as the air we breathe, acting as filters through which everything in life is perceived, without our knowing they even exist.

Initial reactions to earliest experiences, core beliefs remain in place, shaping not just how we interpret life, but how we behave. When positive, core beliefs can be advantageous, but when negative, they stoke fears that create dysfunctional behavior that creates consequences that reinforce the core beliefs themselves—I am unlovable, worthless; people can’t be trusted, will always let me down; the world is dangerous, I will never be happy—self-fulfilling prophecies in an endless feedback loop.

read more

Jesus riding into Jerusalem is an object lesson in only seeing what we are programmed to see. Four distinct groups all see Jesus filtered through the desires and attachments of their core beliefs. The Jewish people and Jesus’ followers see him as a savior coming to fix their problems. To the Jewish and Roman authorities, he’s a threat to their powerbases. Whether Jesus is savior or threat depends on our core beliefs.

We say Jesus is savior, but he’s not here to fix our problems. That’s our job. He’s here to clear our eyes. That’s how he saves. Our way of seeing, our core beliefs, are our powerbases.

Until we let Jesus threaten our powerbases, he will never be our savior.

Showing Our Work

Dave Brisbin 3.23.25

Remember taking math tests in school? Remember how you had to show your work? Remember how you hated that? Wasn’t enough to get the answer, you had to show how you got to the answer. Yes, a right answer, or at least a functional one, is important. But showing your work signaled that you grasped underlying principles that would give you repeatable results, a platform on which to build.

Mathematics understands that the how is at least as important as the what. That any answer is only valid within the context of the process of the solution. How we do what we do defines us and our work.

In scripture, this process is symbolized by the number forty—a time of trial and testing leading to spiritual rebirth, the necessary work of transformation that just takes time. After Jesus’ baptism, he sees the spirit of God and hears God’s voice. A divine download if there ever was one. Yet he is immediately impelled into the wilderness for forty days to face his wild beasts. After the Damascus road vision, Paul spends fourteen years in Arabia for his forty. Elijah after Mount Carmel, the Israelites after the Red Sea crossing, Jacob after the dream of his ladder, the disciples after the resurrection…all faced fortyness after their downloads. But why? Shouldn’t a direct download from God be enough?

read more

However intense, any download is only momentary. Will not last unless we wrestle with the paradox long enough to assimilate, push into muscle memory a single view of two ever-oscillating realities: heaven and earth. There is no other way.

We have to show our work.

The Gift of Doubt

Dave Brisbin 3.9.25

Years ago, at the lowest point in my life, a friend invited me to her church, marking a return to Christianity after fifteen years away. First thing, I booked a lunch with the pastor, and halfway through, across my untouched plate, he said he saw “divine dissatisfaction” in me. Strange phrase. I didn’t see anything divine in my dissatisfaction or speed-questions, but then, there I was. Asking a pastor.

Years later, I looked it up. I’m pretty sure he didn’t know he was quoting a dancer. He was much more a football quoter. But Martha Graham said that artists have a divine dissatisfaction, a blessed unrest, that keeps them marching and more alive than others. Pastor saw that unrest in me. Though it didn’t feel divine or blessed, it certainly was motivating. Kept me marching, desiring, seeking, doubting. I doubted everything I’d ever been taught about spiritual life, which only made me desire it more.

Remember Doubting Thomas?

read more

All Thomas said was that he was dissatisfied with a second-hand report, hearsay. That only a personal experience could break him through to trust the impossible. Thomas is our hero, showing us doubt as a gift. It stokes us with the dissatisfaction we need to admit that even the Bible is a second-hand report. It points us toward our own personal experience, but it’s not the experience itself.

This Lent, can we see our doubt and dissatisfaction not as weakness, but a gift…a divine call past hearsay to a personal experience of the new life Easter represents?

Empowered

Dave Brisbin 3.2.25

Jesus doesn’t save anyone passively, in spite of themselves, beyond their willingness to actively engage a way of experiencing transformed life he calls Kingdom. If we’re waiting for a savior, no one is coming. If we’re waiting for anything, we’re not in Kingdom. Waiting is passive, not yet; Kingdom is always in motion, herenow. Jesus saves by empowering us to act in ways we may have thought not possible or not allowed. He shows us the process of fundamental change, challenging us to make the small choices we can make now to start dominos falling toward radical transformation not yet.

The good news of the gospels is that God is all poured out.

Everything God is and has to offer is already herenow. Nothing withheld…Kingdom within, in our midst. Jesus’ message tells us that we are empowered to accept the everything of God any time and always, and his Way is the unavoidable process of realizing our empowerment, only and always experiential—the choice by increasingly audacious choice or trust.

read more

That is anathema to the Jews who wrote the scriptures from which we extract such a creature as Satan. For Jews, God is unopposable, the One without opposite. No battle is possible, and ha-satan, the adversary, is God’s agent—whether a person, spiritual being, or our own inclination to evil—providing us with the alternate choices that make free will real. But the choice is always ours, and ha-satan has no power over us that we don’t give.

Jesus is telling us we are not victims. Everything we need is right here. The choice is always ours to break through any resistance that would tell us otherwise. Empowered.

The Real Enemy

Dave Brisbin 2.2.25

Would Jesus have been a Republican or Democrat?

What seems like the setup to a joke is being asked in all seriousness. Two weeks into a controversial administration, I’m hearing people ask how a good Christian could possibly vote… How a Christian pastor could possibly support… An Episcopal bishop and a sitting president both state that God is on their side while remaining flatly opposed to one another. Near the end of the Civil War, Lincoln said that both North and South read the same bible, pray to the same God, invoke God’s aid against the other, but the prayers of both could not be answered, that of neither had been answered fully.

Once we see an enemy, we imagine God is on our side, because we only have an enemy if we are certain we are right. An enemy is the wrong one. God is never wrong, so God is on our side, because we are right. Blaise Pascal said that people never do evil so completely and cheerfully as when they do it from religious conviction.

Truth is, the real enemy is not the other tribe—

the real enemy is the certainty that makes the other tribe an enemy.

read more

Jesus refused to be co-opted into any camp. Whatever political beliefs he had are not preserved in the gospels, meaning they were irrelevant to his message. They never created enemies for him because his primary identity was not in camp or tribe, but in oneness with his Father. If we can only see truth in our own tribe, we’ll see enemies everywhere, but we won’t see Jesus. He’s in the space between camps, where the real enemy is not another tribe, but the certainty that makes enemies of everyone else.

Keeping the Faith

Dave Brisbin 1.26.25

One of the best-known stories from the gospels, one that has seeped into collective consciousness, is the story of Jesus walking on water. This and turning water to wine has become shorthand for divine power. It’s natural for us to focus on the literal, but all Jesus’ miracles have spiritual meaning as well, and since most of us will live full lives never walking on water, the spiritual meaning is more relevant. Especially when Peter asks Jesus to bring him out on the water, and we can suddenly see ourselves as participants in miracle making.

But Peter gets out a few steps, sees the waves from his new perspective, and starts sinking, screaming for help. Jesus puts him back in the boat saying, you of little faith, why did you doubt? How many times have Jesus’ words been aimed at us when we’ve expressed the least bit of existential uncertainty? But is doubt as uncertainty really what Jesus is rebuking? The word translated as doubt comes from a root that means twice or again, so we can understand it as second guessing ourselves, wavering in resolve as we ruminate.

read more

We don’t have little faith when we stop thinking we mentally believe. We have little faith when we start thinking again and stop acting. Faith is not thought. It’s acting as if what we say we believe is true enough to carry us on the surface tension of uncertainty. The nonrational ability to act in the presence of doubt, step out of the boat of all our very good reasons why not.

Little faith is not much doubt. It’s the need for much certainty. Keeping the faith is not steely-eyed adherence to mental concept. It’s the embrace of uncertainty, accepting we will never have enough information to step out of our boats. We just do. Over and over. Until trust replaces certainty.

More Big Words

Dave Brisbin 1.19.25

From someone going through a perfect storm of difficulties: I see no evidence of God, but plenty of evidence of the devil. Despite years as a devout Christian, she’s hit the point we all do, over and over in life, the point Karl Jaspers called a limit situation. The moment we realize we’re gonna need a bigger boat. Hitting the limit of our ability to cope, make sense, make meaning—everything that ordered our universe lying in a heap.

Why does God seem silent when evil is so loud?

We can walk into a dilapidated house and say we see no evidence of an architect, but the fact of the house, the space in which we could care for and maintain a home, is the architect’s fingerprint. If the consequences of human action or natural processes like extreme weather or viruses frustrate our agendas, security, and certainty, we label them evil. They overwhelm us, obscuring the order beneath. God is everywhere and everything, the foundation and bones of the house, the floor on which we act. But no matter how badly we neglect the floor, it still exists, if we’re still acting. We can say the news is always bad, but that’s good. Though loud, bad news is still the aberration against the backdrop of good.

read more

Such a non-specific message is not what we want, but all that we need.

The suffering always present in a limit situation is the only experience powerful enough to pull back the curtain of our certainties du jour and show us the next larger reality we may be ready to engage…a spiritual awakening. But as long as we equate our suffering with evil, let it blot out the possibility of good, it can’t show us anything.

The Big Words

Dave Brisbin 1.12.25

I’m often asked about the big words…

The words of Christian doctrine that seem to contradict the nature of God that Jesus called Good News, love itself. Degreeless and indiscriminate love that can’t be altered or avoided, showering on everyone equally—just and unjust alike. Yet Christianity feels exclusive…acceptance withheld unless we believe in an orthodox Jesus, declare him as Lord, obey church rule and ritual. There is heaven for those who perform, the eternal torment of hell for the rest, and at the center of it all stands the cross. Ironically, the ultimate dividing line.

Here’s a big word: propitiation. An English word used to translate the Greek and Aramaic words used by John and Paul to describe Jesus’ death on the cross. It means to appease wrath, regain favor, change the mind of an angry God. In 1611, the King James bible translated the Greek hilasmos and Aramaic husaya as propitiation, but this has become controversial. Later translations use expiation instead—atonement, the extinguishing of guilt. The ancient words can mean both, so which?

read more

None of the big words mean what we think when placed back in the language Jesus and his followers spoke and wrote. We must re-know what they knew. Jesus was laser-focused on love…

The meaning of any big word that contradicts that love is a mistranslation.

Reward and Punishment

Dave Brisbin 1.5.25

An angel was walking down the street carrying a torch and a pail of water. When asked what he was going to do with torch and pail, the angel said that with the torch he was burning down the mansions of heaven, and with the pail, putting out the fires of hell. Because only then would we see who truly loves God.

With no promise of reward or fear of punishment, what is the temperature of our love when there is nothing “in it” for us—no consequence for not engaging.

Everything in us rebels at this. We’re offended if there’s no reward for hard work. Yet Jesus tells us that no matter when we show up, we’re all paid the same at the end of the day—love is its own reward. We’re offended if there’s no punishment for failure, yet Jesus says that sun and rain fall on the just and unjust alike—love can never be other than what it is. We have to scale the wall of reward and punishment before we can ever hope to experience love without degree. Jesus relentlessly works to tear down this wall, knowing how deeply life has embedded it while giving no experience of something as alien as degreeless love.

read more

Life is so uncertain and humans so fragile, we crave certainty as medication, and the paradigm of reward and punishment at least gives some illusion of control. That performing as we imagine God wills, binds God contractually to love and acceptance. But even the slightest vestige of meritocracy blinds us to the possibility of a love that can’t be withheld or altered, keeping us forever striving for what we already possess.