contemplative way

The contemplative way of spirituality is the way of stepping aside from anything and everything we think or feel that would distract us from what is present right here and now–the conscious awareness of God’s presence.

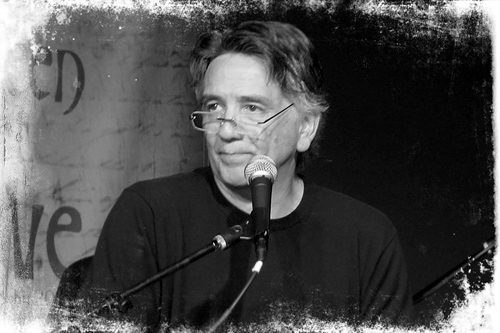

The Life in Death

Dave Brisbin 5.18.25

Two events converged in my mind last week.

My wife and I picked up the ashes of a friend we’d been helping take care of for the past few years…and our faith community turned eighteen years old. Nothing like an anniversary to open the memory faucet, and maybe because of our friend’s death, the serious illnesses of many others, and my own advancing age, my memories were not focused on timelines, but the long parade of people who have meant so much. Those who have stayed, moved on, and especially those who have passed on.

They have been reminding me of the brevity of life, to make my time count. Not morbidly in a pressured way, but gratefully, aware of the gifts they gave me in our short spans together. Each of four men who helped found and lead our community had a particular gift he exuded, lived out most likely unintentionally, and of which I was unaware at the time. It’s perversely true that it’s harder to see the gifts others are giving while they live. Maybe because while ongoing they’re taken for granted, or because always mixed with inevitable faults and annoyances, the prophet is not honored if too familiar.

We don’t know what we got til it’s gone.

read more

To live with presence, passion, humor, devotion is to immerse so fully in life, we step outside the container we will leave at death, realize that all our fear exists only in our minds. Not in life. Or in death. Fear is a mental construct that we can take off like a dirty shirt. We will always fear the unknown at first, but our teachers, living and dead, are showing us in their most unguarded moments, that we can loosen the bonds that hold us inside our fears and experience the life that exists even in death.

Growing Small

Dave Brisbin 12.8.24

What does the story of Job have to do with Christmas?

Any story is a story about risk. We’ve all been at risk from our first breath, but we don’t like to think of ourselves balanced on a razor’s edge of circumstances we can’t control. We work really hard to manage risk, grow as big as we can, accumulate money and materials so risk will have to get through all our stuff before it ever gets to us. Illusion. Risk passes through stuff like ghosts through walls.

Job was big. Had everything a person could imagine—big hedges against risk. So when it all was taken, no one was more surprised than he. He cried out for answers, but when God finally speaks from the whirlwind of mystery and non-answer, Job finally admits his smallness. He had to lose everything to see himself as he was, that working to grow big is just another attempt at the control and invulnerability that will always elude. It’s not who we are as humans, and we’re never complete without accepting who we are. Only in our innate vulnerability do we find the connection that we call meaning and purpose. Job had to grow small to see this.

If you want to find something lost by a child, what do you do?

read more

Jesus and Job found what can only be seen from the standing height of a child, the kneeling height of a servant. Why are so many of us depressed at Christmas? Because we imprint the magic of Christmas from a perspective three feet off the ground and try to find it again from the height of an adult. Our God risks being small, vulnerable for the sake of connection. The only way to find what has been seen by a childlike God is to get on our knees and grow small.

Power of Powerlessness

Dave Brisbin 8.25.24

We don’t have real rites of passage in our culture anymore. At least not conscious rituals that take us through the three essential stages of separation, transition, and reincorporation. In true rites of passage, we are taken from the familiar world we know and plunged into a transitional experience that is betwixt and between the life we knew and the life we will enter when ready. It’s a liminal, threshold experience that disturbs and disorients as it teaches, and when the transition is complete, there is a reincorporation that recognizes our new place in the community.

Babies losing their teeth and debutante balls don’t count, but joining the military certainly does, especially if deployed. But we don’t ritually reincorporate our soldiers back home as other cultures do, leaving us with such high veteran addiction and suicide rates. We still have two traditions that preserve rites of passage—the Way of Jesus and 12 Steps of AA. Unfortunately, we have reinterpreted Jesus’ Way as a system of intellectual belief labeled as faith, losing the original Aramaic understanding. So we turn to the 12 Steps—structure built on Jesus’ original principles.

read more

Our minds create thought-worlds with illusions born out of a lifetime of hurt and trauma. We are captive to these worlds, including illusions of personal power wielded alone against the forces around us to fill implied survival needs. No one gives up power voluntarily, but in Step One we begin to see the truth—that our illusions of power are really our compulsive addictions themselves.

The opposite of addiction is not sobriety, but connection.The illusion is that power is personal, isolated.The truth is that power is shared in connection.

We can give up an illusion.

Falling to Heaven

Dave Brisbin 6.9.24

Everybody wants to go to heaven, but nobody wants to die. Yeah, that’s a country song, but Joe Louis, the great boxer, said it first.

Death is the moment everything we can think of as ourselves, our entire sense of self, falls away. It’s the moment our minds stop thinking, stop imagining ourselves as individuals, separate from everyone and everything else. The irony is, we never feel better, more connected, loved, grateful, meaningful, fulfilled than moments when we lose our sense of self—whether in meditation, prayer, or an intense, peak moment, like falling in love. When our sense of self falls away, the anxiety of aloneness falls with it. And yet, that falling away of self is exactly what we fear in death, because we can’t imagine who we’d be when we can no longer think of who we are.

Heaven is the state of absolute connection, but we must die to get there—die to our sense of self. The mind is the sole repository of ourselves-as-separate, so as long as we’re in our right minds, we are not in heaven. An elder in an ancient monastic community of desert Christians taught that if you see a young monk by his own will climbing to heaven, take him by the foot and throw him to the ground… Early Christians knew that heaven is not a goal to achieve, but a reality to realize: we are all connected, always. We don’t acquire that, we relinquish all that obscures it. Climbing to something we already possess only intensifies our illusion of self and individual control, the opposite of heaven.

read more

The moment we become willing to stop clinging to an imagined identity as a separate self, become willing to die to all we think of ourselves, to all we think at all, we lean back and start falling.

Everything we fear we will lose or never gain is in the falling.

Feeling God’s Pleasure

Dave Brisbin 3.17.24

What do humans look like when they break through their own thought-created worlds—all about survival, controlling competition—and become present to the real world around them?

I remembered the movie Chariots of Fire, based on a true story set around the Paris Olympics, 1924. It contrasts two runners, a British Jew, Harold Abrahams, and a Scottish Christian, Eric Liddel. Abrahams has been embittered by the prejudice he’s suffered as a Jew, and runs for revenge, driven to win and prove superiority over those who despised him. Liddel, China-born to missionary parents, has been preparing to return to the mission field even as he gained stardom in rugby. His sister, Jenny, just as driven as Abrahams in her religious zeal, is dismissive and critical of his athletics; they distract from God.

Liddel tells Jenny, “I believe God made me for a purpose, for China…but he also made me fast…and when I run, I feel his pleasure. To give it up would be to hold him in contempt.” Abrahams runs for revenge. Jenny runs for duty and obligation. When Liddel runs, he feels God’s pleasure.

read more

Liddel was only 22 years old. How’d he do that?

Running was just another place where he felt God’s pleasure: sheer oneness and connection. But seems he also felt God’s pleasure when he greeted his fellow runners, unconcerned at that moment for the race itself, until that became the source of God’s pleasure. Twenty years later, he was still feeling God’s pleasure in China, working with children in the WWII internment camp where he died. Wherever he went, whatever he was doing, he felt God’s pleasure, changing everything.

I don’t know how he felt all this at 22. But with intention and a bit more time, we can all feel it too if we wish.

Listening to Rocks

Dave Brisbin 2.25.24

When Jesus rolls into Jerusalem the week of his execution, there are major mixed emotions in the crowd of onlookers. The common folk are chanting and cheering as the authorities, both Jewish and Roman, hang back, concerned over any shift in power. Jewish leaders tell Jesus to quiet the crowds, but Jesus replies that if these were silent, the very rocks would cry out. Just pretty poetry? Something deeper?

He seems to be echoing both King David and Paul who said that all creation testifies to truth and can’t be silenced or ignored. More poetic license? Astronomers say they have heard the sound of a black hole singing: a massive black hole in the Perseus cluster is emitting sound centered on a tone 57 octaves below middle C. And microwave background radiation, radiation from celestial bodies and nebulae can also be heard as sound, as music. Creation is singing. We just have to be tuned to the right frequency.

read more

To engage our moments at this level is to become aware of the deeper connection that is experienced as a sense of wellbeing, a metaphysical ok-ness for which the automatic reaction is gratitude. When you feel the smile spreading across your face without your permission or thought, when you suddenly see in the smallest detail you may have seen a thousand times, the thrill of something deeper, you are praying this prayer. Significance in insignificance. Divine truth in the most ordinary moment when your prayer is your awareness—tuned to hear the rocks sing.

Ashes

Dave Brisbin 2.18.24

We’re still in the first days of Lent. If you didn’t grow up in a liturgical church, you may not know about ashes on foreheads, confession and penance, fasting and giving up candy bars or some other treat for forty days. And even if such memories are part of your past, you may have as much to unlearn as others have to learn about Lent.

For nearly 1,800 years, the forty-day period before Easter is meant to be a time of preparation. Originally the preparation for baptism of new converts, it was ported over to Easter as an annual time of preparation for the new life of rebirth. Mirroring Jesus’ forty days in the wilderness, the deprivation and suffering of Jesus’ experience is emulated, but why? As children, we understood it as punishment and penance for our sins, wiping our slates clean for God, but this relatively passive and vicarious approach is not what Jesus experienced during his fortyness.

read more

The fortyness of Lent is meant to be a similar, ritually difficult preparation for transformation. But if that’s our intent, we need to reframe it: not as a negative punishment or penance, but as positive, affirmative action we intentionally take to clear out distractions, take a dive into our shadow selves, and create an ideal interior environment for spiritual breakthrough. The fasting and deprivation of Lent is not punishment, but an opportunity to lower our egoic guards and awareness threshold—allow God’s presence to show through. We can use Lent as a crash course to silence and simplify enough to see what is really meaningful in our moments and any interior limitations keeping us from that meaning.

Training Wheels

Dave Brisbin 2.11.24

What churches and religion inevitably forget—as does every human group—is that their laws, doctrine, and practice are not ends, truth in themselves, but pointers, guides to non-rational truth that must be personally experienced, never bestowed.

Thomas Huxley said that new ideas begin as heresy, advance to orthodoxy, and end in superstition. Belief systems practiced for a length of time follow this curve, and Christian thought is no exception. The practices that Jesus taught and his followers called the Way, heretical to most, were understood as a way of life that prepared individuals to experience the paradoxical truth of God’s love. But as the movement matured and institutionalized, life practice became ritualized, and the theological ideas that had grown around them were legalized into orthodoxy. Eventually, law and ritual were believed to have supernatural power, ends in themselves rather than pointers to spiritual experience.

read more

Jesus is teaching us that law is not fulfilled in obedience or righteousness in ritual practice. Legal compliance and ritual observance mean nothing in themselves, but everything when they have become the deepest purpose of a transformed heart. To believe otherwise is to miss the Way entirely, remain focused on conformance rather than transformance…as if training wheels are permanent, the highest expression of riding a bike, and not a limitation—the outward badge of an inward inability to fly.

Teach Us to Pray

Dave Brisbin 1.28.24

Familiarity breeds contempt usually means that the more we know people, the more we can lose respect and judge more harshly. If contempt seems too strong a word, at least the more familiar things become, the more they blend into the wallpaper until we don’t even see them anymore. And when those things are religious scripture and doctrine, we may be so saturated that we believe we know things we have never considered on our own: accepted as children or under group pressure, such teachings became familiar before ever teaching us how to live spiritual lives in a physical world.

And what is more familiar than the Lord’s Prayer? Even those not steeped in Christian tradition are familiar with it. We learned it as kids, recited it—but what is this wallpaper saying? Is there anything to learn beyond mere recitation? We know the words: Our Father in heaven, hallowed be your name. Your kingdom come, your will be done, as in heaven, so on earth…

read more

The five lines of the prayer form the steps of a process that starts with becoming unfamiliar again with everything we think we know. Clearing an interior space allows us to see the reality of the sacred in the ordinary details of life and begin to match our values to God’s, only knowable when our sense of separate self is lost in present action. Released from that sense of separateness, the victimhood of the past, we realize a new connection, always herenow.

If we can become unfamiliar again, see these words again for the first time, we can stop reciting them and start living the path they describe. Or better, recite them as a reminder to really live.

Growing Up

Dave Brisbin 1.21.24

Disciples of a spiritual master come to his home only to find him on hands and knees in the front yard. He tells them he lost something of great importance, so they fall in to help search, hands and knees, eyes straining. After some time, they ask where he had it last, where he might have lost it. Oh, he says, that was inside the house. Then why are we searching out here? Because the light is so much better…

We laugh, but as crazy as that sounds, isn’t this exactly what we do spiritually? The master is trying to teach his students that we all want to conduct our existential search where it’s comfortable…how it’s comfortable. In our strong suit, under conditions where the light is good, and we can hold on to the illusion of control. We want to dictate the terms of the search, and even the nature of the thing searched for. Much safer to search for a god we imagine we understand.

read more

In his famous love chapter, Paul said when he was a child, he acted and reasoned like a child, but when he became a man, he put away childish things. He places this metaphor against the fact that we can only see spiritual reality dimly, but when the “perfect” comes, face to face. We think he’s talking about heaven, but Jewish context is always this life herenow. When the perfect comes is any moment our house of cards, our world of opposites collapses, and for an instant we see the oneness, the sole substance behind our opposites.

For Paul and Jesus that substance is what we call love, the ultimate reality we’ll never find until we grow up and out of the need for certainty—willing to search in mystery where the light is not so good.